What are Fragrance Pills?

During the Tang and Song dynasties in China, the literati would prepare various fragrant pills using scented materials such as magnolia, lychee peel, cypress seeds, and agarwood. These fragrant pills were made according to the principles of “the emperor and his officials” and the rules of preparation, in order to produce pleasant scents that could soothe both body and mind. These pills were usually the size of green beans and were placed in incense burners, heated by charcoal to release the fragrance. They could also be burned directly or carried on one’s person for personal use.

For literati, fragrant pills were not just used to purify their study or bedroom spaces, but more importantly, they were used as a means to invite friends to enjoy the elegance of life together. Fragrant pills served as a medium to enter the spiritual world and explore the realm of human culture. It was a way to appreciate the refined arts through the sense of smell, and to create a social atmosphere where friends could gather and enjoy each other’s company.

This is a series of experimental works that are based on the olfactory experience of Chinese incense blending, and are presented as visual records.

On average, a person breathes around 23,040 times per day, and the odor molecules in the air flow into our body, surrounding us and influencing our emotions in various ways.

Some people attempt to use pleasant fragrances to enhance our experience of positive emotions, such as perfumes and air purifying products. However, fragrance designers and artists who are not satisfied with the superficial “pleasant” or “unpleasant” experiences, have begun to pursue a deeper, more spiritual influence.

In 2012, the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York hosted an exhibition titled “The Art of Scent: 1889-2012”, which was the first museum-level exhibition dedicated to olfactory art. The year 1889 in the title refers to the year when modern chemical techniques first allowed for the extraction of fragrance molecules such as vanillin from plants, which greatly facilitated the production and development of perfumes due to their easy accessibility and low cost.

From this perspective, “Meditation In Incense” can be regarded as the first olfactory-themed art exhibition in domestic art museums in China. In fact, China began the systematic study of fragrances as early as the Tang and Song dynasties, if not earlier. There are vast ancient texts such as “Xiang Pu” and “Xiang Cheng” that contain a wealth of knowledge and understanding of fragrances by the ancients. From a philosophical perspective, they developed a unique concept of fragrance based on “four qi” and “five flavors”, which is completely different from the Western approach to fragrances.

Fragrance is abstract and fleeting, making it difficult to capture. While isolating fragrances as a standalone artwork is a positive attempt, the methods and meanings behind it are worth exploring and questioning. This is because fragrances cannot exist independently of physical space. Today, the renewed interest in olfactory art comes from the exploration of fragrances that are “fleeting” and cannot be recorded. Each piece in the exhibition is also a constantly changing entity that transforms with the changing seasons, phenology, temperature, humidity, and other environmental factors, leading to an uncertain future…

The ancient Chinese practice of “intention” rather than “form” may be a more feasible approach. They applied philosophical and natural scientific thinking beyond fragrance, successfully establishing a far-reaching fragrance system. By analyzing and observing the substances that emit these fragrances, they summarized the concepts of “four qi” and “five flavors” – cold, cool, warm, hot, sour, bitter, sweet, spicy, and salty – which opened the key to the application of natural material fragrance molecules. For example, the “Plum Blossom Fragrant Pill” made by the ancients: plum blossom is cool and astringent, and is blended with fragrances that are warm, cool, sharp, pungent, and sweet, such as osmanthus, fennel, sandalwood, lingling, and pine resin mixed with honey, creating a fragrance that resembles that of plum blossom. None of the fragrances used in this recipe are actually related to plum blossom, but the fragrance is designed to emulate the characteristics of plum blossom.

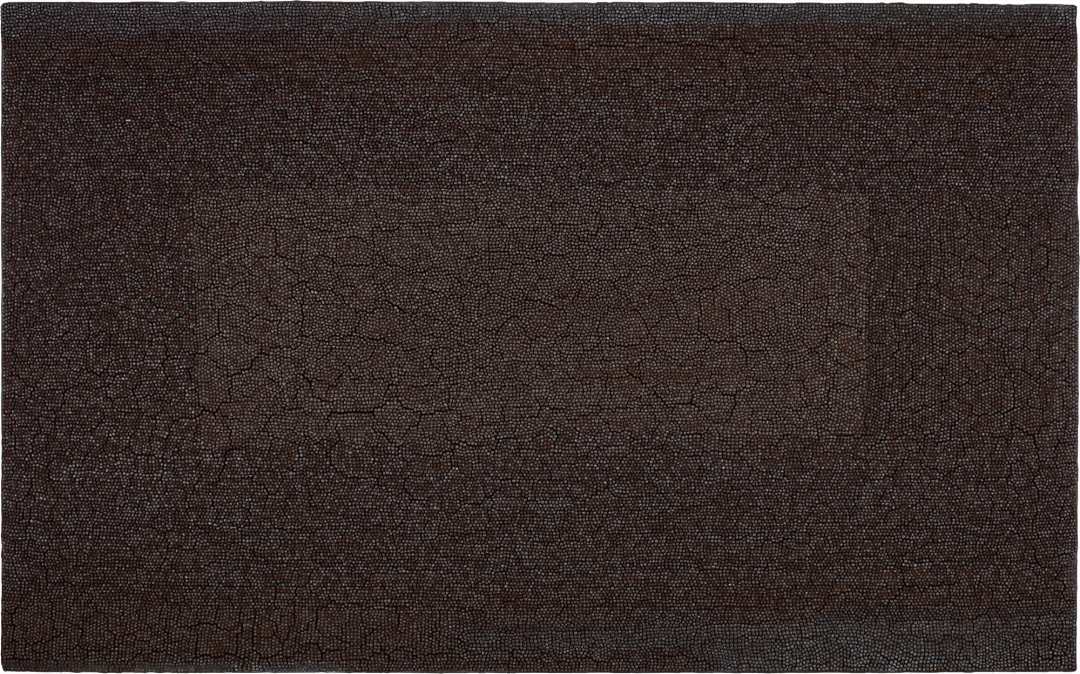

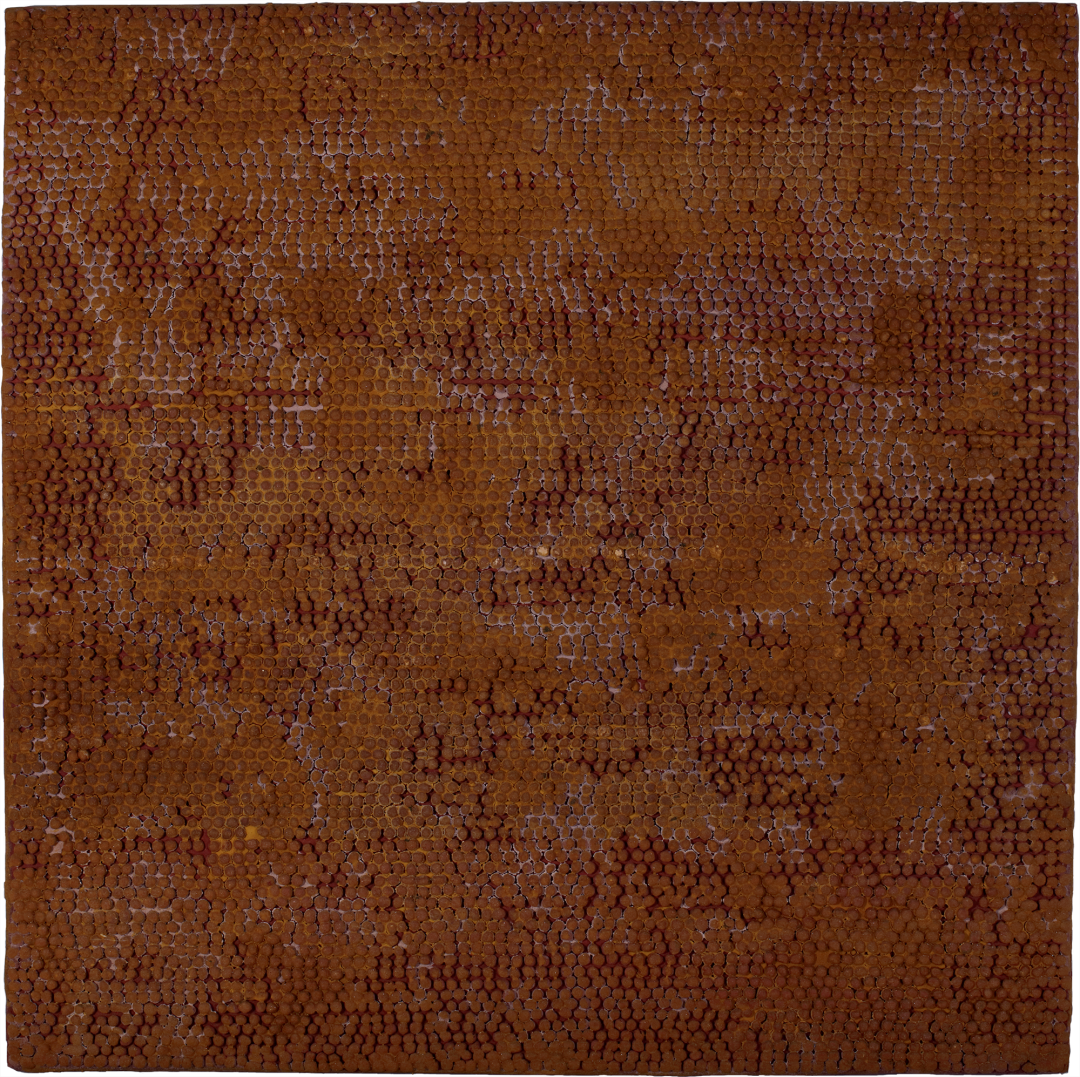

This is called “incense blending”, a method that was born out of learning and understanding nature. The vast research texts left by history undoubtedly are treasures for my creative work today. Following this vein, I try to create an “organic” connection between objects and their inherent fragrances in my works. For example, the work “Counting Pills – 84,000” carries the Buddhist characteristic number (84,000 Dharma Gates), but it was not intentionally arranged. The dense and fearful arrangement of fragrant pills in the picture cannot be fully appreciated without the occasional mysterious fragrance emanating from the “Eastern Land”. It creates an atmosphere of vastness and inclusiveness that immerses us in the universe.

Hegel believed that beauty is the sensuous manifestation of the idea in natural objects, the merging of the idea with the objective object. The highest form of the idea is life and spirituality.

The names of the works in the exhibition are almost all numbered, which is a “realistic” record of the number of fragrant pills, but also reflects a philosophical aspect that transcends meaninglessness and abstraction. In the artist’s creative process, through several hours of quiet production and counting, they enter into a state of “mindful walking” similar to that of a monk, producing insights that are full of classical style and philosophy, such as “peaceful and far-reaching”.

The olfactory culture in China, with fragrance as its main subject, has a long history that can be traced back to ancient times. However, the olfactory field in contemporary Chinese art can almost be described as a blank slate. On the one hand, contemporary artists lack an understanding and sensitivity to olfactory art, and rarely incorporate fragrances into their creative considerations. On the other hand, the lack of skills required for olfactory art also hinders the production of works that delve deeper into the world of fragrances. As a result, the sporadic works in this field are often limited to conceptual explorations, and are unable to fully connect with deeper themes such as history, society, time, form, etc., with fragrance as the main subject.

The creation of the artworks in “Meditation In Incense” exhibition was born out of this context. Mr. Ouyang Wendong believes that the rich connotations contained in traditional Chinese culture are all manifested in the fragrance culture system.

One of the original intentions behind the creation of these artworks was to preserve and present precious things and our most outstanding insights (traditional Chinese fragrance culture) in a new way, so that the public can experience “tradition” in an “alternative” way. By contemplating how the unique Chinese worldview governs our inner selves, we can ask ourselves whether it is just history, what it will pass on to us, and how it will lead us into the future.

My perspectives

by/ Ouyang Wendong

Objects and I cannot be separated and interact through the six senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and mind. Fragrances, objects, and my inner self are mutually contradictory, forming a journey of the spirit for my “odorized form”.

To add another dimension to visual art and to end the loneliness of fragrances in olfactory art.

My daily life is mundane and specific; I sort, chop, and grind the fragrant materials that I collect from different places. Each ingredient carries its own spirit and emits an irreplaceable scent. For example, the big yellow from the deep mountains of the Qinling range, with a slightly bitter and sweet scent reminiscent of the dampness of the earth; the agarwood from the Wuzhi Mountain in Hainan, with a faintly sweet and cool scent, as if protecting the travelers who venture through the miasma-infested jungle; and the lustrous green frankincense, which smells even more refreshing than citrus, and reminds me of the lone tree on the gravelly land along the red sea coast where it was nurtured, a place unsuitable for human habitation.

“How can grapes grow among thorns? Yet, I see grapes among the thorns.” Perhaps the scent of frankincense burning in the censer held by the priest before each Mass in the church is where the divine love is suddenly realized. Huang Shangu, one of the four Su-style scholars of the Northern Song dynasty, who was fond of fragrances and entered into Daoism, was placed in a shabby room in a bustling marketplace during his exile. He befriended fragrances and named the small house “Noisy and Quiet Studio”. It is unknown whether the studio would recall Qu Yuan, who ate fragrant flowers for sustenance when he was exiled to the banks of the Xiang River with “autumn orchids” as his only adornment.

As I manipulate these materials, each a world unto itself, I am reminded of my own small existence and the grand yet orderly redemption it entails. I find tranquility in the mundane task of counting out each and every incense pellet, from one to two, to thousands and even to none at all. Just like Duchamp’s famous saying: “I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my own taste.”

Impressions from the audience

I like it. Coming from a background in sculpture, the artist’s understanding of space adds a dynamic and fluctuating dimension to the two-dimensional visual presentation. It’s a wonderful experience to feel still and meditative.

——Jing

This exhibition is meant to be experienced in person, much like attending a concert. Photos only serve as documentation.

——Gui Ting Ye

Meditation in Incense exhibition embodies the spirit of Zen, which is very interesting! The intangible scent is transformed into something visible. The fragrance guides people directly into the present moment. The eighty-four thousand incense pellets present countless moments of the present.

——Zhou Yan

This exhibition exceeded my expectations. The artworks that incorporate different fragrances not only refresh the distance, movement, and emotions of viewing art, but also blur the spatial boundaries between two-dimensional and three-dimensional works.

This is perhaps the furthest attempt in the conceptual field of the Tang and Song Dynasty’s combined fragrance art. The gathering of one million incense pills, with a particular fondness for the scent of eighty-four thousand methods.

——Mr. MuShan

The artwork directs our attention to our sense of smell and to the state of being without sensation. The state of the incense pills and the state of creation are precisely about forgetting external desires. One by one, forgetting even the fragrance and the numbers, forgetting everything, and just doing this one thing, one enters a state of Zen.

The harmonious interaction between the conflicting tendencies of seeking inwardly and outwardly is also a reflection of the Eastern cultural value of self-cultivation through the practice of seemingly meaningless, repetitive, and tedious tasks.

——Duan Mu

Click the link below to visit Today Art Museum’s official website